A new web portal is opening up access to data about UK soil and its properties. Envirotec asked Russell Lawley of the British Geographical Survey (BGS), who manages some of the content and development aspects of the site, about how it is used and how it might help consultants working in areas like brownfield development and the environmental sector.

CATCHING the momentum of the ‘big data’ trend, and the current popularity of such initiatives at government level, the UK Soil Observatory (UKSO), launched in May, provides a hub for free-to-view and free-to-use information about UK soils. It is hoped the datasets and analytical tools provided will increase access to data that could be used for research and other purposes.

It has been brought together by a number of leading soil research institutions, including the CEH, BGS, JHI and Cranfield University, who have contributed much of the current data. The site also includes free resources such as the Ordnance Survey Terrain 50 product, which has been reprocessed to provide a wide range of terrain classifications relevant to soil, letting users mix and match different types of data.

Much of its appeal is its potential to grow as users contribute and upload data and maps, and it is also being described as “a facility to engage with policy makers, the soil-research community, environmental professionals and the public”.

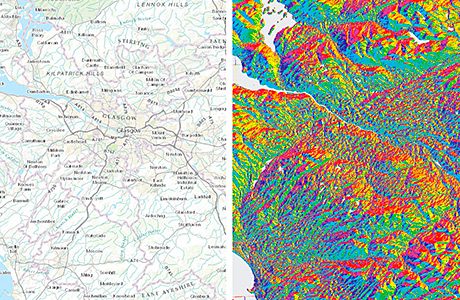

Data can be viewed in a number of ways. A “map viewer” tool lets you move a UK map around with a mouse, clicking to bring up menus from which you can add data layers, letting you filter the map data by organisation or by different parameters such as soil type, biodiversity, pH and so on. The site has started out with 115 layers supported.

“One of the ones I like doing is ‘hill shade’ and ‘aspect’,” says Lawley. “You get this dataset with blue and pink shades, and if you set the transparency right, you can see how soil changes with the landscape – the differences between the soil at the bottom or top of a hill, or how it varies with the climate or land use.”

The various contributing institutions organise this data in their own way, and so this had to be converted to a common, INSPIRE-compliant format for the UKSO, efforts that were funded by NERC.

Contributed datasets

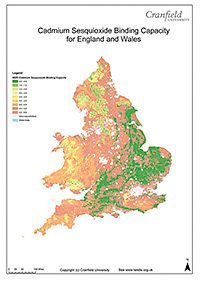

One of the datasets on board so far is Soilscapes for England and Wales, which draws on the much richer National Soil Map of England and Wales, a resource of the Land Information System (LandIS) at Cranfield University, said to be the largest environmental information system of its kind in Europe. It provides spatial mapping of soils at different scales in addition to information about its properties and agro-climatological data.

All the map data is in hi-res (600 DPI) and can be screen-grabbed from the site. If people want a richer level of detail, they can contact the organisations concerned and request it, though often this comes at a price (25p per km2 in the case of Soilscapes for England & Wales).

There is also a huge amount of data being generated by automated sensors. Increasingly sophisticated ones are employed on tractors, and there are projects like LIDAR, which uses a laser mounted on a plane to scan the ground and measure elevation.

The BGS bought a plane 6 or 7 years ago which has been used to gather a lot of geophysical and radiometric data about Devon and Cornwall (the intention was to cover the UK but this proved too expensive). This data has been incorporated in the UKSO, providing detail about the distribution of elements like potassium, thorium and uranium.

Meeting point for experts

So far Lawley says he knows of two mineral prospecting organisations which are using UKSO, as the tool can provide a good starting point for beginning to analyse an area of soil, to see what’s been extracted from it.

The farming community could use the data but also provide a lot of data, he says. Information about soil type and its properties can be used to support sustainable agricultural practices, as well as maintaining the UK’s carbon balance and helping with environmental services like flood protection.

“The more data we push out, the more we get, and the better soils get treated,” says Lawley, alluding to the tendency in the UK to abuse our best quality soils, under pressures such as the need for housing.

Advantages to sharing data

In the brownfield and remediation arena, a lot of consultancies do work and gather knowledge that remains confidential, for commercial reasons. But Russell believes there may be many advantages to sharing data between organisations in the manner of the UKSO. If the information is more out in the open it, he speculates, it might lead to people having a less fearful attitude towards the state of a piece of land; less “I’ll pretend this doesn’t exist” and more “this area has a problem with PCBs” or “this area has been remediated”.

People will also become more comfortable with the fact that a lot of the minerals we associate with industrial activity – and may be fearful about, like arsenic – also occur naturally and are often not harmful in this form.

It seems likely the general public will struggle to understand the data, but there are plans to introduce school-friendly areas, for example. The map viewer has a facility called “contribute” which supports flickr-style uploads – Russell says it currently has lots of images of people’s patios, “which is lovely, but not very useful scientifically”. And some people with a different context for understanding soil might be invigorated. “There are a lot of gardeners in the UK who understand soils as well as any scientist, in terms of what it’s good for and so on.”

The potential of the tool for professionals working in areas like remediation seems relatively unexplored so far but Lawley is excited about its potential. “We want the environmental sector to run with this data,” he says. “It’s great when people phone up with problems or ideas for better ways of doing things.”