While many more people are now aware of the problem of outdoor air quality, there are still many who believe they are safe once indoors – in an office, car or on public transport. This is not always the case and the following article looks at the relationship between indoor and outdoor air quality, and is partly written by measurement specialist Air Monitors.

The government has published draft plans to tackle urban air pollution and other organisation such as NICE have published an air pollution guide, so it is clear that urgent action on air pollution is necessary and possibly imminent.

The NICE guidelines were developed for local authority staff working in transport, planning, air quality management and public health. The guidance is also relevant for staff in healthcare, employers, education professionals and the general public. Covering road-traffic-related air pollution and its links to ill health, the guidelines aim to improve air quality and so prevent a range of health conditions and deaths.

Many local authorities would comment that they are already implementing many of the guideline recommendations, but refer to budgetary constraints on issues that involve upfront costs. Pressure is mounting therefore on the UK government to increase funding for measures that will have a significant effect on urban air pollution. In particular, there is a need to address the emissions from diesel vehicles which are responsible for high levels of particulates and nitrogen dioxide in the UK’s towns and cities. Speaking at the recent IAPSC Conference at AQE 2017, Roger Pitman from TRL said: “There is now a greater focus on evidence based action plans… local authorities should say what their monitoring ambitions are and if that necessitates more funding, the Air Quality Annual Status report should say so.”

The NICE guidelines recommend the inclusion of air quality issues in new developments to ensure that facilities such as schools, nurseries and retirement homes are located in areas where pollution levels will be low. Local authorities are also urged to consider ways to mitigate road-traffic-related air pollution and consider using the Community Infrastructure Levy for air quality monitoring. There are also calls for information on air quality to be made more readily available to the public.

Local authorities are being urged to consider introducing clean air zones including progressive targets to reduce pollutant levels below the EU limits, and where traffic congestion contributes to poor air quality, consideration should be given to a congestion charging zone. Importantly, the guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring to measure the effects of these initiatives – as part of the consultation process, NICE was looking for evidence of successful measures and specifically rules out “studies which rely exclusively on modelling.”

All of the initiatives referred to in the NICE report require monitoring in order to be able to measure their effectiveness. However, most local authorities do not currently possess the monitoring capability to do so. This is because localised monitoring would be necessary before and after the implementation of any initiative. Such monitoring would need to be continuous, accurate and web-enabled so that air pollution can be monitored in real-time and made available to all stakeholders.

One example of a solution is the AQMesh measurement ‘pods’ produced by UK air quality instruments maker Air Monitors. Networks of AQMesh pods are said to have many advantages, being small, lightweight, quick and easy to instal. These air quality monitors are able to monitor all the main pollutants, including particulates, simultaneously, delivering accurate data wirelessly via the internet. Air Monitors says AQMesh ‘pods’ are significantly lower in cost, both to buy and to run, than reference air quality monitoring stations. However, they still represent a ‘new’ cost. A recent report from the Royal College of Physicians points out that such costs are trivial when compared with the NHS costs associated with the adverse health effects caused by poor air quality.

During a recent conference on air quality, AQE 2017, the speakers were asked about the ‘elephant in the room,’ by a delegate referring to the government’s air quality consultation. However, in response Prof. Rod Jones from the University of Cambridge said: “I thought you might be referring to indoor air quality.”

Air pollution publicity has largely focused on what is measurable outdoors. In contrast, indoor air quality is rarely in the media, except following occasional cases of carbon monoxide poisoning or when worker lethargy or sick building syndrome are reported. However, it is important to understand the relationship between outdoor pollution and indoor air quality.

Smarter ventilation

Poorly ventilated buildings tend to suffer from increased carbon dioxide as the working day progresses, leading to worker lethargy. In many cases HVAC systems bring in fresh air to address this issue, but if that air is in a town or city, it is likely to be polluted – possibly from particulates, if it is not sufficiently filtered, and most likely from nitrogen dioxide.

Ventilating with outdoor air from street level is most likely to bring air pollution into the building, so many inlets are located at roof level. However, data from recent studies indicate that the height of the best air quality can vary according to the weather conditions, so it is necessary to utilise a ‘smart’ system that monitors air quality at different levels outside the building, whilst also monitoring at a variety of locations inside the building. Real-time data from a smart monitoring network then informs the HVAC control system, which should have the ability to draw air from different inlets if available and to decide on ventilation rates depending on the prevailing air quality at the inlets. This allows the optimisation of the internal CO2, temperature and humidity whilst minimising the amount of external pollutants brought into the indoor space. In circumstances where the outside air may be too polluted to be used to ventilate, it can be pre-cleaned by scrubbing the pollutant gases in the air handling system before being introduced inside the building.

The implementation of smart monitoring and control systems for buildings is now possible thanks to advances in communications and monitoring technology. AQMesh pods can be quickly and easily installed at various heights outside buildings and further units can be deployed internally; all feeding near-live data to a central control system.

Indoor particulates

Another example of indoor air quality monitoring instrumentation that has been developed from outdoor measurement technology is the ‘Fidas Frog,’ a fine dust aerosol spectrometer developed by the company Palas. Frog is a wireless, battery-powered version of the popular, TÜV and MCERTS certified Fidas 200. Both instruments provide simultaneous determination of PM fractions, particle number and size distribution, including the particle size ranges PM1, PM2.5, PM4, PM10 and TSP. Frog is said to be ideal for investigating indoor areas where particulate pollution is a concern – in train stations and in the Underground for example.

Following a debate in the House of Lords and a Sunday Times investigation, Simon Birkett from Clean Air for London wrote to Sadiq Khan on 9 July 2017 concerning ‘tube dust’ urging him “to do much more, much faster to: understand the health risks; warn passengers and potential passengers; and reduce people’s exposure to it.”

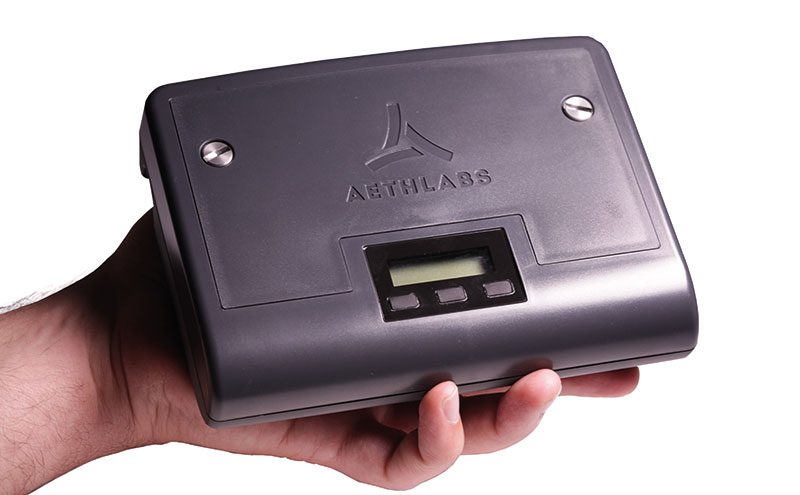

Evidence of outdoor air pollution contaminating indoor air can be obtained with the latest black carbon monitors that can distinguish between the different optical signatures of combustion sources such as diesel, biomass, and tobacco. The new microAeth® MA200 for example, is a compact, real-time, wearable (400g) black carbon monitor with built-in pump, flow control, data storage, and battery with onboard GPS and satellite time synchronisation. The MA200 is able to monitor continuously for 2-3 weeks. Alternatively, with a greater battery capacity, the MA300 is able to provide 3-12 months of continuous measurements.

Official advice

The government’s Clean Air Zone Framework, published in May 2017, refers those seeking advice on monitoring options to the document Local Air Quality Management Technical Guidance (TG16)3. The latter, it says, provides advice on the monitoring options available, the considerations to bear in mind to obtain value for money, and what the monitoring aims to achieve. For example, in the case of NO2 measurement, the document says “two technologies have been approved – the reference method (chemiluminescence) and diffusion tubes but other approaches may be appropriate for specific campaign work”.

Air Monitors argues that the prospects for its AQMesh pods are exceedingly good, citing ‘excellent’ performance demonstrated in the UK and overseas, “at a fraction of the cost of reference stations”. They are also said to be quick and easy to fit, providing near-live data via the cloud, so in conjunction with reference stations, they could be said to be ideal for monitoring applications required by Clean Air Zones. As described above, they can also be fitted indoors so that the effects of outdoor air pollution on indoor air quality can be measured, and therefore managed.