Dr Hugh Falkner of the AEMT (Association of Electrical and Mechanical Trades) looks at the circular economy and the motor repair industry

According to a 2016 report by McKinsey, the average European uses 16 tonnes of resources a year, of which only 40% is recycled. This is clearly not sustainable, so the idea of the Circular Economy was born to develop new business models that will help us to move away from this situation. Some motor manufacturers are already looking ahead to consider what this might mean for their businesses, and CEN/ CENELEC is already engaged in early standardisation activity.

To understand more about what the Circular Economy is, and why it is relevant to the motor market, we need to look back at the history of motor efficiency regulation. What emerges is an unexpected story of how the motor repair industry turns out to be a leading example of how the Circular Economy can work in practice, and further the business opportunities that this presents.

Product eco-design regulations

In Europe, the Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) are called the Eco-design regulations, but when you look carefully at the methods for assessing just how far it is justifiable to push legislation, the Eco bit is not quite complete. This is because while the financial lifetime costs of ownership to the user, and the environmental emissions to water and air, are taken into consideration, it is now recognised that the Eco-design analysis doesn’t adequately address the important question of product durability and the need to reduce material consumption.

The circular economy

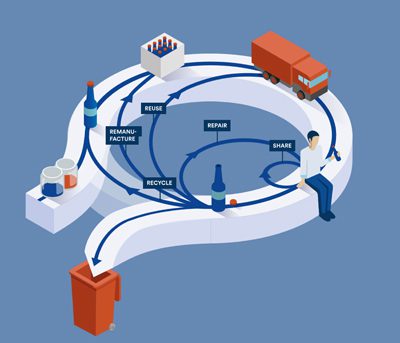

This circular economy aims to “minimise waste through reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products”, ideas which look to be helpful in achieving the right energy:material balance in any future eco-design regulations impacting motors.

What this brings is more of a focus on material use, which compliments the traditional focus on product energy consumption that the motor repair sector has supported. It is fundamentally different to the Linear “Take-make-dispose” economy that underpins most material use.

In practice, reducing global material consumption might be about making things that use less material, last longer, use less premium materials, or simply be easier to repair or recycle.

As an example, Figure 1 shows how a bottle might travel around several loops between first use and eventual landfill. In one sense, “all” that we have achieved is to extend the time between a product’s raw materials being dug out of one hole, used, and then put back into another hole. But it does reduce the amount of raw material that needs extracting and processing, and so conserves resources for future generations. This resource life extension is the best that can be hoped for from most manmade systems. This is what industrial equipment repairers have always done – in fact it’s hard to think of any other sector placed so centrally to take their part in the circular economy. In terms of the above diagram, the repair sector sits in the second smallest loop, with tighter loops being the most efficient in terms of minimising waste.

How the circular economy benefits the conventional economy

Governments recognise the benefits of the circular economy through the following:

– More local, and higher skilled jobs

– Less imports, and so improved balance of payments

– Exports of remanufactured parts

– Less exposure to fluctuating material prices or material scarcity

As we will see, the motor repair sector is a very good example of what is possible, and can demonstrate the value of these benefits to the economy.

It will be important to moderate the circular economy ambition to what is best overall for both the motor user and the environment.

In an October 2016 presentation, the European Committee of Manufacturers of Electrical Machines and Power Electronics (CEMEP) is similarly positive about the Circular Economy, but equally cautious that any new regulation must take account of the advances in motor technology, and maintain a balance between energy efficiency and material use considerations.

The motor repair industry emerges as a leader

In the report by the Ellen MacArthur foundation on how Scotland might benefit from the circular economy, six diagnostics (numbered in bold below) were given to show the different aspects of the circular economy as they might appear in practice. Here the motor repair industry is tested against the same diagnostics, and surely qualifies to call itself part of the circular economy:

1. Circular product design and innovation – product re-design promotes standardisation and modularisation so that they can be easily disassembled, and the value of resources is retained within ‘tight’ reverse circles.

a. A commonality of designs that means that it is possible to keep replacing motors from many different suppliers, without carrying large and expensive inventories of spares.

b. The capability to manufacture spare components in order to keep obsolete or unusual models working.

c. The careful sorting of scrap materials to maximise sale value.

d. Valuable materials like copper and permanent magnets extracted from DC brushless motors for re-use.

2. Product re-use, repair and remanufacturing – ensuring longevity of use requires manufacturers to enable re-use and remanufacture products in the system for as long as possible. This tips the balance away from ‘production’ to ‘maintenance’. It also demands new competences to ensure the effective collection and sorting of products along reverse cycles.

a. Repair of products is what the industry does.

b. An underlying philosophy of stretching life and reliability, avoiding obsolescence

c. Many repairers offer condition monitoring services to help optimise maintenance interventions and reduce unplanned downtime.

3. Innovative business models – creating value-adding business propositions around better-designed, long-lasting products. Disruptive business opportunities based on performance (e.g. shared ownership, hire and leasing and pay-for-use models) can compete successfully against low cost, ownership-based linear models. They also enable much closer interaction with customers (‘users’) and increased personalisation and customisation.

a. “Keep you running services” are already offered that incentivise the service provider to ensure reliable operation, through pre-emptive monitoring, repair and replacement programmes. This is a classic indicator of the circular economy in practice.

b. Advise on reasons for failure to enable operational changes to be made to extend lifetimes.

c. Making small changes to motor design, such as winding and insulation design, to better match real life operating conditions.

d. The wider use of low cost condition monitoring sensors that will indicate when service is required, allowing intervention before failure.

4. Renewable energy and materials substitution – while circular systems help optimise efficient resource use, they also avoid unnecessary exploitation of resources in the first place. Switching from fossil-fuels to renewable energy, and substituting non-renewable and scarce resources for renewable alternatives are important aspects.

a. The sector is not involved in design. It is also careful to keep products as closely as possible to their original design by avoiding unnecessary substitution of inferior parts.

5. Effective supply chain and cross-sectoral collaboration – a circular economy demands changes at all levels of the economy to drive collaborative solutions. Policy alignment, incentives, industry standards, access to finance, infrastructure and education are all vital elements.

a. A highly developed infrastructure that provides local 24hour service.

b. Rapid turnaround times to reduce financial and environmental costs of motor failures.

c. Suppliers of new motors work hand in hand with motor repairers – it’s a symbiotic relationship where both have a shared long-term incentive of doing what is best for the customer.

d. Testing of iron and no-load losses as a useful proxy to formal efficiency measurement, giving the security that the repaired motor is fit for service.

e. The AEMT, with EASA, has led the way on defining best practice in repair, giving user confidence in the conforming repairers.

6. Re-use of waste, heat and energy – treating otherwise wasted outputs of business processes as the inputs for new processes reduces costs, boosts productivity and opens up new commercial opportunities.

a. The repair sector is not involved in the “Use phase” of motors.

CEN/CENELEC standardisation activity relating to the circular economy

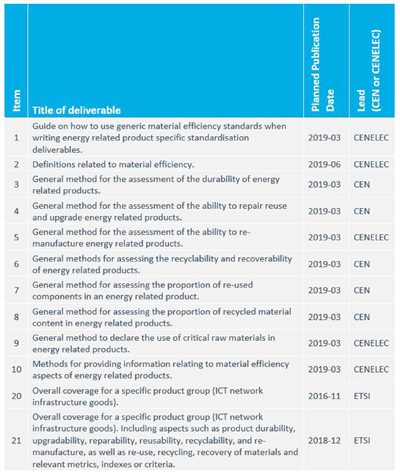

The new EU Circular Economy package demonstrates the European Commission’s view of the importance of the circular economy. One outcome of this is Mandate 543, accepted by CEN and CENELEC, which has the aim of balancing energy efficiency considerations in Eco-design regulations with considerations of material used, in particular at the end of life stage. The European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform gives an excellent overview of their many activities.

This standardisation work (Figure 2), will be instrumental in setting the “ground rules” for further work and possibly regulations on the Circular Economy, and so early involvement in their evolution will be important to make sure that the views of the repair industry are made known alongside those of other stakeholders.

UK activity in the circular economy

Given the importance of the circular economy, there are many organisations active in the area, including:

The Ellen MacArthur foundation supports a wide range of initiatives that “works with business, government and academia to build a framework for an economy that is restorative and regenerative by design”, and has a wide range of resources for inspiration.

The Waste and Recycling Action Programme (WRAP) is a charity working with waste in all sectors of the economy, and is particularly active in waste minimisation and recycling. Just one activity of interest is the Electrical and Electronic Equipment Sustainability Action Plan 2025 (ESAP 2025), a key part of which concerns product durability, and how to communicate this to buyers. Although aimed at the domestic sector, it would be fascinating to explore how these concepts might be applied to the industrial sector, especially in the light of competition from lower cost and potentially less durable motors appearing on the market.

Positioning the sector as a leader in the circular economy

From this initial look at the circular economy, the motor repair sector in the broadest sense, which includes pumps, fans, and compressors, emerges as being in many ways “ahead of the pack” in demonstrating how the circular economy works in practice. Going forward there are three challenges that should be embraced to make the most of this pole position:

1. How to share the sector knowledge and experiences with other sectors.

2. How to engage with other existing bodies so that the repair sector can learn to do even better.

3. How to promote a position of leadership in the industrial circular economy.

This could just be a fascinating time for the repair industry to raise its profile, and show leadership in helping the economy to meet one of the biggest challenges facing our futures.