In banning plastic drinking straws, coffee cups and other single-use plastic, the UK Government and NGOs seem to be ignoring the really big issue – the exportation of waste plastics that are ending up in the world’s oceans, says UK recycling firm Axion Polymers.

While politicians continue to follow the current UK media hype surrounding these ‘local issues’, they are failing to see the bigger picture and implement strategies that could provide economically-viable solutions to the growing pollution crisis.

“The actual tonnages of these minor fractions of single-use plastics are tiny in comparison to the BIG issue,” says Keith Freegard, Director of Axion Polymers, a Manchester-based plastics recycler. A viewpoint that is shared by other industry experts.

Asia: Merely a detour en route to the ocean?

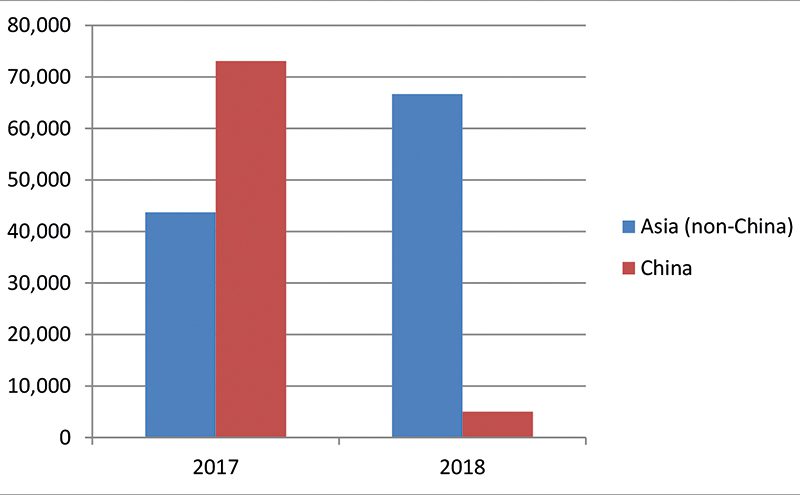

The UK traditionally exports around 450,000 tonnes per annum of plastic packaging waste to Asia. The graph opposite shows the dramatic fall in exports to China in the first quarter of 2018 compared to the same period in 2017 and huge jump in exports to other Asian countries.

China’s National Sword ban on imported plastic waste has resulted in hundreds of containers being shipped to other Asian countries, such as Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia and Sri Lanka.

“82% of ocean plastic originates in Asia Pacific countries,” continues Keith. “If we were worried about standards of residual waste disposal in China, then we should be even more concerned about waste treatment infrastructure in these less-developed countries. This, of course, begs the question ‘how much of the 450,000 tonne pa is actually unrecyclable?’

“Sadly I think, along with many others in this industry, that quite a significant percentage of plastic waste from the UK householders’ kerbside collection stream is ending up in rivers, and subsequently the oceans. Rather than wasting taxpayers’ money on a plastic straw consultation, what UK government should be doing is finding out exactly how much of the exported waste to all those countries is being turned into really high-grade plastic.

“And what is happening to the fraction that is not being properly recycled? Around 15 to 20%, I guess. Is that going straight into the oceans? If it is, we’ve got a dreadful system!”

Sharing Keith’s views is Jessica Baker, Director at Chase Plastics Ltd, a UK plastics reprocessing company with more than 50 years’ experience. Jessica asserts: “Banning straws and other single-use plastic when the oceans are filling with our exported plastic is like fiddling while Rome burns. It will do very little to change the problem of plastics in our oceans.

“If we think we have found a new home for the low grade mixed plastic waste that China did not want, should we not be concerned that it might be inundating countries that already have a much poorer environmental record than China, and will struggle to cope to actually reprocess all this material?

What’s actually needed?

“The reality is that plastic needs to be sorted into its separate polymers and formats in order to facilitate final reprocessing back into reusable pellets, but as long as we keep sending poorly sorted plastic overseas for reprocessing a significant proportion of this mix will end up in open landfill, the rivers and then oceans overseas.”

The solution, she suggests, is to make products more recyclable, collect these and reprocess them in the UK, adding: “Exported plastics should be of a sorted, single polymer stream or format so that overseas reprocessors do not have to re-sort it and throw out what they can’t use. Only this is going to address our contribution to the problem of ocean plastic.”

Documentation shortfall

Phil Conran from 360 Environmental echoed these concerns. “It is clear that plastics are being exported that would fail the Transfrontier Shipment Regulations quality requirements if containers were checked. We know that even farm plastics are currently leaving the country in significant quantities and these can contain over 50% contamination. One of the issues we face is a very loose export control system with little information available to the Agencies before material is exported. Exporters of green list material have no legal requirement to submit documentation and consequently, the Agencies are left looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack. There is urgent need for export regulatory reform alongside measures to address the vast amount of unrecycled plastic that make a much greater contribution to global ocean litter that these small volume items.”

A proposed solution

So what can be done? In conclusion, Keith suggests the authorities should follow the price of exported plastics to accurately measure the true levels of contaminants in waste plastics leaving the UK. He points out that some low-grade mixed plastics cost a ‘gate fee’ to export; yet will contain high percentages of waste in the bales. Many exporters are simply accessing ‘low-cost, poorly-regulated waste disposal routes’ in third-world countries. What we need is a much more rigorous and thorough methodology to accurately measure and quantify the split between ‘recyclable’ plastics and the tonnes of ‘unrecyclable’ waste in the containers leaving our shores.

“In the UK we’re already 15 to 20 years late in reacting to this issue and turning it into an economic growth opportunity. Unless our government recognise what dreadful environmental damage this huge waste export stream might be doing, and start to put in place some clear legislative drivers that underpin the growth of an economically viable plastics recycling industry, only then can we be truly responsible for the waste that we produce.

“It’s no longer good enough to export it overseas, and hope for the best, we’ve got to be seen to be recycling as much as we can through well-regulated businesses operating under our own legislative waste structure,” he adds.

“This is so much more important than cotton buds and straws. We are sending our collected plastics out of sight and out of mind. The UK Government has to address this moral issue – and stop wasting time on a drinking straw consultation!”