An independent review of the UK’s current progress and plans in relation to achieving net zero – titled “Mission Zero” – was published on 13 January.

Led by former energy minister Chris Skidmore, the Net Zero Review was commissioned in September by Liz Truss, and received over 1800 responses, concluding in December.

Engineering and other stakeholder groups seem in broad agreement with the report’s conclusions that “there is no future economy but a green economy.” Local government group Blueprint Coalition believed that it “correctly diagnoses the multitude of barriers holding back local net zero ambition.”

It outlines the apparent economic opportunity offered by net zero, an undertaking that is now an “international race” for capital, skills, and the industries of the future.

“Delivering net zero is the industrial revolution of our time,” said the document, which claims the UK “would see 2% additional growth in GDP through the benefits from new jobs, increased economic activity, reduced fossil fuel imports and cost savings (for example cheaper household bills).”

While praise is due for the progress made since the UK set a net zero target, says the review, it is also clear that “we need a new approach to our Net Zero Strategy.” And this seems to involve more of an emphasis on stable, long-term goals rather than “piecemeal, short term projects”.

But the strategy itself is alright, and is “still the right pathway”, concludes the review, we just need to get a move on, as “delay is a significant risk” and “the benefits of decarbonisation are larger if it is done sooner.”

In terms of concrete actions, the report presents 129 recommendations, including outlines of 25 actions to be taken by 2025 – which include scrapping planning rules for solar panels, and legislating to phase out gas boilers by the earlier timeline of 2033 (rather than 2035) – and ten “priority missions” for 2035.

The review said it was “calling for a new mission, to bolster energy efficiency for households.” But The Guardian seemed unimpressed with a mere two-year rescheduling of the gas-boiler phase-out, noting also that the review falls short of “a nationwide house-by-house programme of upgrades”, which campaigners have called for, and also doesn’t set out clear options for homeowners on how to improve their energy efficiency.

“Stopping new boiler sales a couple of years earlier is a start,” said renewable energy firm Good Energy CEO Nigel Pocklington, “but recent history shows the technology can move faster than policy.”

“Falling costs of solar, storage, heat pumps and electric vehicles are all outpacing predictions.

“If you need to replace a boiler, choosing a heat pump can already be the same total price with lower costs to run. The main costs we should be concerned about are the those of inaction.”

The existing Heat and Buildings Strategy doesn’t go far enough to help householders, says the report. It’s too costly for low-income households to meet the upfront capital costs of heat pumps and other improvements, and access to finance is an issue.

Energy thrift

But an uptick in energy efficiency ambition is recommended. For example, that all non-domestic buildings attain an EPC rating of B or above by 2025, and that residential properties should achieve the same by 2030. It also calls on the government to “urgently reform EPC ratings to create a clearer, more accessible Net Zero Performance Certificate (NZPC) for households.”

Technology’s potential contribution to energy efficiency seemed to be overlooked in places. Glynn Williams of Grundfos commented, “To get to better energy efficiency, buildings need more than the best insulation; they must address energy inefficiency at source. Hydraulic balancing of inefficient heating systems, for instance, could save up to 20% a year on bills for an initial outlay of around £120.”

“Gas bills cost the average household £575 a year, so a nationwide roll-out of hydraulic balancing could save up to £3.1 billion annually.”

Technology obstacles were also flagged by Johnson Controls, which suggested companies can’t hope to make impactful changes to buildings’ energy efficiency without smart tech, referring to problems like the legacy infrastructure of gas heating, and the lack of interactive control available.

Home hydrogen hesitancy

Rather than provide all-out endorsement of hydrogen boilers in residential properties, the report suggested that government “should continue the hydrogen heating community trials, to inform decisions on the role hydrogen can play in heating”, and recommended that the government update its analysis of the whole system costs at the end of 2023, “to ensure that the case for economic optimality and feasibility still holds”.

But the report recommends a number of actions in relation to hydrogen’s deployment generally, to scale up production and incentivise investment, including the development of a 10-year delivery roadmap by the end of this year.

Onshore wind and solar – “the cheapest forms of generation” – should also be ramped up, and it recommends scrapping planning rules for solar and increasing solar generation fivefold by 2035. Taskforces should be set up to aid this effort.

But it’s not just about finding alternatives energy sources, suggested SulNOx Group’s Nawaz Haq, but finding ways to decarbonise existing ones. “Like it or not, fossil fuels are not going to disappear overnight, and unless we put as much effort into lessening their impact as we do on finding alternatives, we will never win the race to net zero.” His own firm provides “responsible solutions towards decarbonisation of liquid hydrocarbon fuels.”

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage is a net-zero technology that the report pegs as “ripe for development” and it recommends that “government must act quickly to re-envisage and implement a clear CCUS roadmap, showing the plan beyond 2030.” In this effort, “government should take a pragmatic approach to cluster selection. This means allowing the most advanced clusters to progress more quickly.”

The oil and gas industry needs to “accelerate the end to routine flaring from 2030 to 2025”, one of the 25 short-term actions recommended by the report. The sector should also publish “an offshore industries integrated strategy” by the end of 2024, giving detail on matters including “roles and responsibilities for electrification of oil and gas infrastructure.”

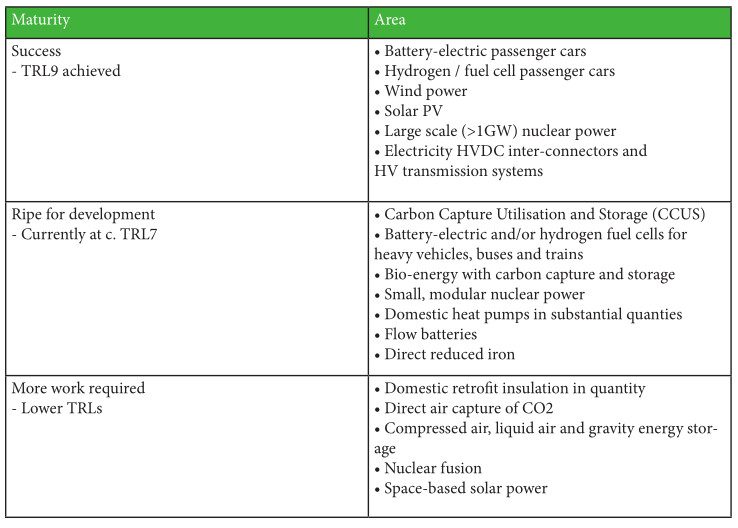

But much of the technology crucial to net zero remains at a low readiness level, says the report (see table 1, below), and these longer-term innovations have been starved of funding, which tends to favour the well-proven. This funding gap was described as “the valley of death” at a recent roundtable of the Royal Society, and the Mission Zero document recommends a number of ways in which R&D funding might be reorganised and long-term opportunities better identified.

It calls for the creation of a roadmap, by Autumn 2023, that clarifies the direction of travel for R&D and its funding, in relation to net zero, all the way out to 2050.

Transport is the biggest contributor to UK carbon emissions, but the report barely touched on it, and The Guardian said this reflected “the absence of government strategy on the subject”. The newspaper also noted no mention of plans to roll out a nationwide system of charging points – currently a big gap when it comes to envisaging how electric transport will work.

Skills are often cited as an obstacle to net zero, and that we don’t have the manpower to meet the necessary targets for building retrofits, and the report advised that the government should “drive forward delivery of the Green Jobs Taskforce recommendations, and the commitments from the Net Zero Strategy, reporting regularly on progress starting by mid-2023.”

There was also mention of “helping SMEs to upskill” via a recommended ‘Help to Grow Green’ campaign, “offering information resources and vouchers for SMEs to plan and invest in the transition.”