Accusations that China might be pursuing an aggressive industrial espionage strategy against other nations appear to have gained credibility following comments made to the Guardian in October by a former employee of Pelamis Wave Energy, a now-defunct Scottish renewable energy manufacturer.

The firm’s Edinburgh office fell victim to a burglary on a night in March 2011, during which four or five laptops were stolen. Written off at the time as a routine theft, the matter was given little further thought until photographs surfaced a few years later, appearing to show a technology being tested in China. It bore a strong resemblance to the Scottish firm’s principal project, a large gherkin-shaped machine called Pelamis, a sophisticated system for generating power from wave energy.

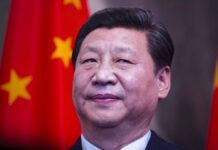

Fuelling speculation of foul play was the realisation that the break-in had occurred two months after a visit to the Pelamis facility by then vice-premier of the state council of China Mr Li Keqiang, now the country’s premier, the only stop-off on his trip outside London.

Max Carcas, who was a business development director at Pelamis until 2012, has spoken publicly about the affair for the first time. In comments published by the Guardian he said – referring to the photographs – that while some of the details may be different, “they are clearly testing a Pelamis concept.”

Details of the break-in also support the view that it was targeted and purposeful. According to Carcas, whoever broke in went straight to his old firm’s office on the second floor, bypassing the ground floor offices and a first floor office of Siemens. Quoted in the Guardian he said he could infer all sorts of things but “do not want to say.”

Pelamis went into administration in November 2014, having failed to raise the funding needed to continue. The eponymous wave energy technology had taken 17 years and £95 million to reach that point.

The Chinese product, the Hailong 1, seems to have been built by a commercial firm, part of the Chinese Shipbuilding Industry Corporation. Questions sent to the Chinese Government by the Guardian, requesting information about the origins of the Hailong 1, have so far remained unanswered.

The intellectual property for the technology is not protected in China, making the possibility of a legal challenge brought by the Scottish or UK government untenable.