Microbiologists from Tomsk State University (TSU) in Siberia have become the first in the world to isolate the bacteria Desulforudis audaxviator, using samples taken from water located deep underground in Western Siberia.

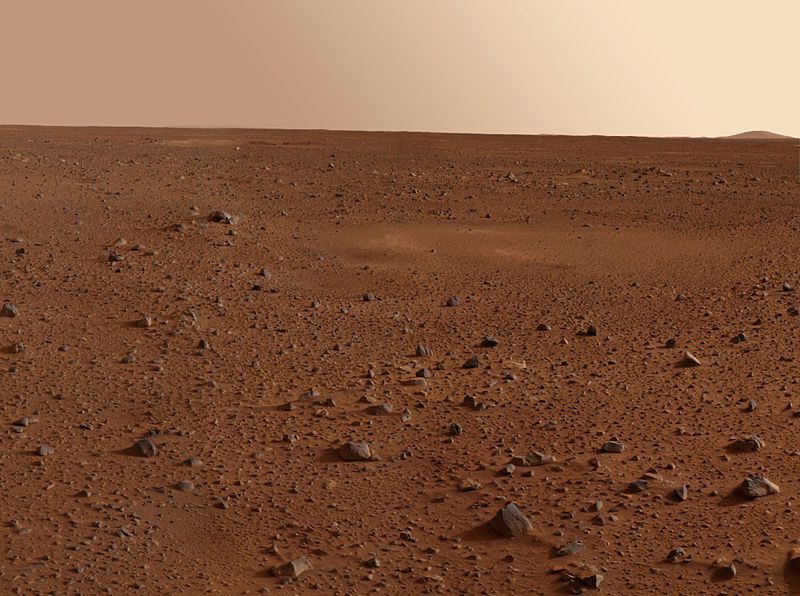

Interest in the bacterium has been high given its ability to derive energy from its environment in the absence of light and oxygen, making it a candidate for a type of life theoretically possible in space, or on a planet like Mars. But its isolation has proven elusive until now. The results are published in the journal ISME.

The existence of Desulforudis audaxviator, living deep underground, became known more than 10 years ago, according to Olga Karnachuk, head of the TSU Department of Plant Physiology and Biotechnology and lead author.

The genetic trail was first picked up by American scientists in 2008 via the DNA of a microorganism found in the mine waters of a gold mine located in South Africa. Sampling was carried out at a depth of 1.5 to 3 km, where there is neither light nor oxygen. Not so long ago, it was believed that life in these conditions was impossible because without light there is no photosynthesis – the energy-conversion process that appeared to underpin all food chains. But this assumption was later revealed to be incorrect. One of the clearest pieces of evidence in this respect is the “black smokers” – the hydrothermal vents found on the ocean floor. But, in contrast to those, the Desulforudis audaxviator lives underground in complete solitude. After the publication of an article by American researchers in the journal Science, scientists from different countries began a search for the bacteria.

Its DNA was found in water samples in Finland and in the US, but no one could isolate the bacterium itself. Its elusiveness was explained by the assumption that it only divides every thousand years.

TSU microbiologists were able to isolate the Desulforudis audaxviator, working with samples found in the underground waters of a thermal spring located in the Verkhneketsky District of the Tomsk Region. The scientists had extensive practical experience in the isolation of complex sulphate-reducing bacteria.

Sulphate-reducing bacteria are among the most ancient microorganisms on the planet. This diverse group of prokaryotes is distinguished by the ability to receive energy in the absence of oxygen due to the consumption of sulphates and the oxidation of hydrogen or simple organic compounds. Among sulphate-reducing bacteria, there are thermophilic microorganisms that can live and multiply at temperatures from + 50°C to + 93°C.

The studies were conducted jointly with TSU’s partners at a testing centre for biotechnology affiliated with the Russian Academy of Sciences, a group with extensive experience in DNA sequencing, said Olga Karnachuk. A group of Moscow experts under the guidance of Professor Nikolai Ravin looked at the samples that TSU scientists had selected during searches for oil wells in the north of the region. The DNA of the bacteria was found in the samples taken in White Yar, in Western Siberia.

Some time after that, TSU scientists managed to isolate the bacterium and obtain new data about it. First, it became known that the bacterium divides more than once every thousand years, actually once every 28 hours – that is, almost daily.

Second, it turned out that Desulforudis audaxviator is almost omnivorous: in the laboratory, it “ate” sugar, alcohol, and much else. According to the researchers, the bacterium appeared to thrive particularly when feeding on hydrogen, from which it receives the most energy. In addition, it turned out that a previously held assumption, that oxygen is destructive for an underground microbe, does not in fact hold true.

And third, the group identified the structure of the bacteria, and found that it travels widely throughout the world, thanks seemingly to tiny bubbles – or gas vacuoles – and this is seemingly a similar mechanism to the swim bladder of certain types of fish. However, the movement pathways of the bacteria remain somewhat mysterious, since the underground reservoirs in which the DNA of the microorganism was found were geographically isolated. The scientists’ hypothesis is that the bacterium travels through the air via small particles of aerosol, and falls to great depths from the surface of open water bodies.

And finally, another surprising fact is that the genome of the bacterium found in Siberia is almost identical to the DNA of the bacteria from South Africa.

“It shouldn’t be like that, a mystery that we don’t understand,” said Olga Karnachuk. “The fact is that mutations are always present. Even when the same bacterium is cultivated in the laboratory, over time differences in DNA appear. In this case, they do not. And it is not clear why. The answer to this question is connected with some basic fundamentals of living cells that have not yet been studied, therefore the explanation of this genetic similarity is a matter of the future, something that scientists still have to work on.”

The Latin name of the bacterium Desulforudis audaxviator comes from a quote from Jules Verne’s novel Journey to the Center of the Earth. His hero, Professor Liddenbrock, shows a Latin inscription: “Descende, audax viator, et terrestre centrum attinges” (“Descend, brave traveler, and reach the centre of the Earth”).