John Whitehurst, UK business manager with minerals and lime producer Lhoist, offers predictions on how new recycling and reuse targets will affect the types of waste being produced. He considers future challenges and opportunities for the energy-from-waste (EfW) sector

No-one likes to see waste being burnt and even policymakers tend to view this as a necessary evil. But the truth is, at the moment we have no choice, for two reasons. Its inevitability is partly assured by the Government’s Resources and Waste Strategy, which contains a target of further dramatically reducing municipal waste going to landfill to 10% or less by 2035. And secondly, the option of shipping waste off to faraway places like China is disappearing.

That’s why the waste strategy admits: “…incineration currently plays a significant role in waste management in the UK, and the Government expects this to continue.” In fact, the strategy predicts an additional two million tonnes of EfW capacity will come on-stream by 2020.

Incineration growth

The use of incineration has grown exponentially in recent years. In 2012, there were only 24 EfW plants in England. Today, we have almost double that number. The latest UK statistics show that the tonnage of waste being incinerated for energy has quadrupled in the last four years alone, a significant milestone being reached last year when more tonnage went to EfW than into landfill.

The majority of councils that are also waste authorities either already have an EfW facility or are planning to get one. Investors and waste companies take the view that the UK still has considerable under-capacity for EfW. It is anticipated that the number of plants will at least double by 2030.

But clearly, with lots of recycling and reuse targets now being set, we have to ask ourselves: what’s the composition of waste going to be in five years’ time and what will that mean for the sector?

The changing shape of waste

In general, we are seeing a trend away from burning rubbish from traditional black bags, in the form of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW). The newest plants are signing contracts to use refuse derived fuel (RDF) or, in some cases, solid recovered fuel (SRF), which derives from materials recycling facilities (MRFs).

RDF and SRF are the best fuels to use. The waste is shredded, baled and ready to go. It has been produced to a specific calorific value and offers consistent burning characteristics, which are valued by plants. Lhoist is the world’s largest lime producer, supplying our products for flue treatment for EfW and biomass plants all over the UK, so the chemical composition of waste is of significant interest to us. As you start to take plastic away you can incorporate other materials which also have a high calorific value, but their combustion will produce different by-products. These, in turn, will potentially require new techniques and reagents to reduce unwanted emissions.

Pollutants and plastic

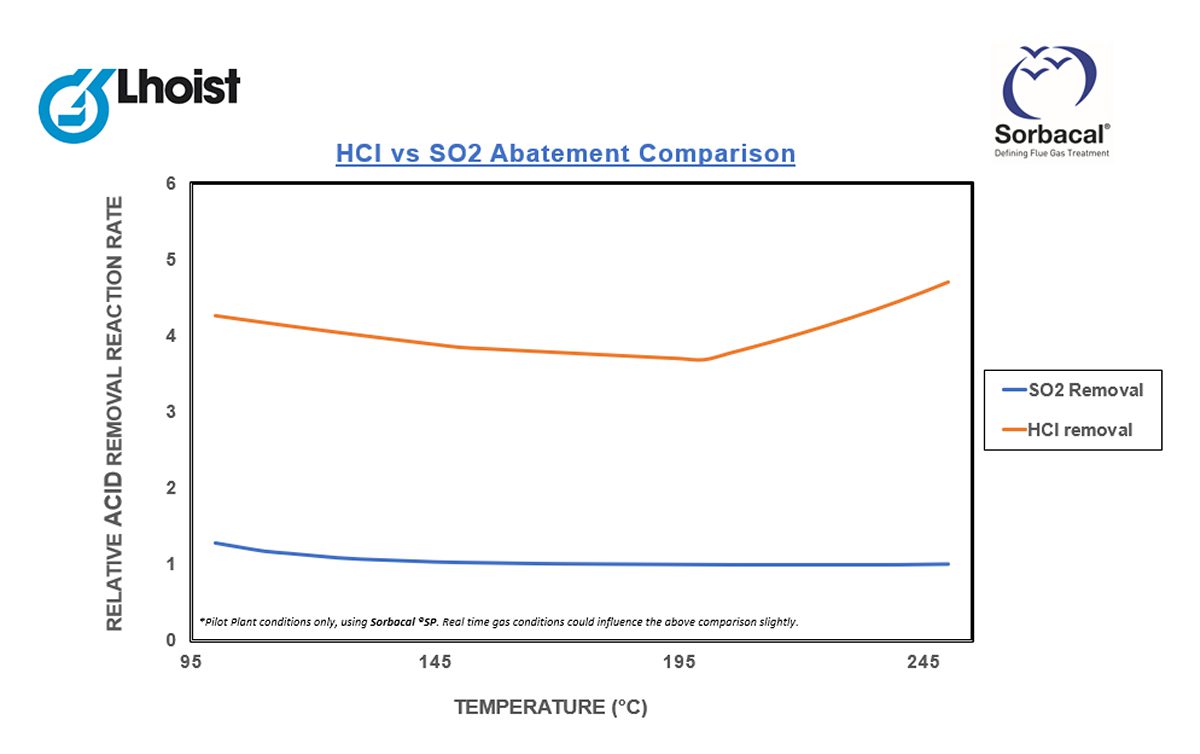

In EfW plants, the main pollutants relevant to hydrated lime are the acidic pollutants: hydrogen chloride (HCl), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and hydrogen fluoride (HFl). Burning a higher proportion of plastics produces more HCL and less SO2. For existing operational plants, the ratio of HCl to SO2 is typically about six- or seven-to-one. In my view, if you look at projects coming on stream in the next three to five years, that ratio is going to be much closer to one-to-one. In fact we have just provided reagent estimates for a series of plants that will see more SO2 than HCl in their waste stream, an indication that fuel contracts for future projects are being agreed with changes to waste compositions.

Plants coming on stream now are signing contracts with fuel suppliers that anticipate more waste being sorted and less plastic in feedstock, but we can’t exactly predict what the changes will be. At Lhoist, we are already bringing to market the next generation of reagents, designed to assist plants to cope with varying proportions of sulphur, chlorine and fluoride in their emissions and to make the most of existing flue-gas treatment technologies as well as newer technologies.

This will help make sure that plants remain within their permitted emission limits and the conditions set by performance warranties, as their feedstock fluctuates.

Stricter emissions limits

There is an additional challenge coming down the line: Emissions limits set by the Environment Agency will inevitably become even more demanding, reflecting tighter EU rules. In my view, unless some of the older, legacy EfW plants invest in new technology now, they could face the prospect of needing expensive bolt-on solutions in three to five years’ time, or will even risk going out of business.

We will need solutions that innovate both in terms of flue-gas treatment technology and reagents. This will require far more collaboration across the EfW sector, notorious for its silo working. Government support may also be forthcoming.

The Defra waste strategy says: “We continue to welcome further market investment in residual waste treatment infrastructure. We particularly encourage developments that increase plant efficiency, and minimise environmental impacts whilst upholding our existing high standards of emissions control.”

Gasification: Still to take off?

Lhoist supplies its hydrated lime-based products to the most high-tech EfW plants, using advanced conversion technology (ACT). Here, waste is heated to high temperatures in low or no oxygen environments, so that it breaks down, producing a combustible by-product called syngas, which can be used to generate electricity.

This process, of which there are variations known as gasification or pyrolysis, was encouraged by subsidies and seemed to promise a cleaner method of operation but it is currently used by fewer than 25% of EfW plants.

Many struggled to get running on a consistent and reliable basis and some plants that were originally permitted for ACT have, during the permitting process, changed back to traditional incineration. I think it’s fair to say that it has not taken off as quickly as people thought and that the jury is still out.

Home economics

As Defra’s new strategy acknowledges, waste should be viewed as a commodity from which value can be extracted – not as a cost drag. You could ask why the UK is currently exporting three million tonnes of RDF a year to other countries to feed into their industrial furnaces and power stations? Why aren’t we gaining the economic benefit ourselves?

There’s a growing view that we can do something more useful with unwanted plastic than turning it into heat to make steam and power. Exciting start-up companies are developing processes that can be used to make plastic into biofuels and other valuable products. British Airways, for example, has partnered with Velocys, to design plants that convert waste, including plastic, into a clean-burning jet fuel. The initiative will contribute to the airline reducing its net greenhouse gas emission by 50% by 2050.

It’s true that the EfW sector has a steep hill to climb, in terms of public perception. Most people are unaware that plants work to strict emissions standards, tightly enforced by the Environment Agency and that bonfire displays are more harmful to the environment than waste incinerators, in terms of particulates and dioxins.

Even when members of the public understand the difference between steam and smoke and are not basing their opposition on myth or misconception, they may have other environmental concerns, and these may be justified. Location is important. Plants need to be sensitively sited if they are to avoid inevitable objections. For example, on the basis of intrusive lorry movements.

Northern promise

There’s far more of an acceptance of EfW plants in Scandinavia and that’s not because they are smaller and less visible – some of them are very large. You could even say that they are popular. The reason is that the plants are nearly all used to provide people with cheap heating from district heating systems. That’s an option that we too rarely take up in the UK. We install the pipework to fulfill permitting requirements but don’t usually connect it to anything. That is a terrible waste.

That missed opportunity is acknowledged by Defra’s waste strategy. It notes that that much higher efficiency levels – typically of around 40% – can be achieved if EfW plants harness their heat output in addition to generating electricity. Very few do – often because they cannot find a customer for waste heat. The strategy draws attention to Heat Networks Investment Project from

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) – a £320 million capital fund to help develop waste-powered district heat schemes.

It also says that Defra will work with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government so that and the National Planning Policy Framework supports the Waste Management Plan for England.

The waste strategy makes clear that incineration, especially when providing combined heat and power, has a vital role in meeting the UK’s medium-term strategic requirements. As recycling capacity increases and waste sorting becomes more sophisticated, new technologies are applied to packaging as public awareness increases – a phenomenon observable following the BBC’s Blue Planet series in 2017.

There is another factor relevant to the future shape of the EfW sector: By 2025, there will be no more coal-fired power stations and it is widely predicted that the UK will struggle to make up the energy shortfall.

Currently, the EfW sector contributes less than 10% of energy to the grid. With a predicted doubling of the number of EfW plants in the next ten years, that number could go into double figures – reducing the significant greenhouse gas emissions that are inevitable as a result of methane generation when waste is buried in landfill and making a welcome addition to wind and solar sources. It’s another valuable contribution that waste incineration could make to the circular economy.

For further information about Lhoist and Sorbacal visit www.sorbacal.com.