A big problem with the disposal of nuclear and electronic wastes is that the process wastes precious metals such as gold and platinum-group metals, which are key metals in computer chips. Nagoya University in collaboration with Tokyo Institute of Technology have discovered that a solution to this pressing environmental and technological problem may lie in a pigment named Prussian blue. Using their technique, gold could be extracted from electronic waste, such as smart phones, in amounts 10-80 times more than can be obtained from natural ores.

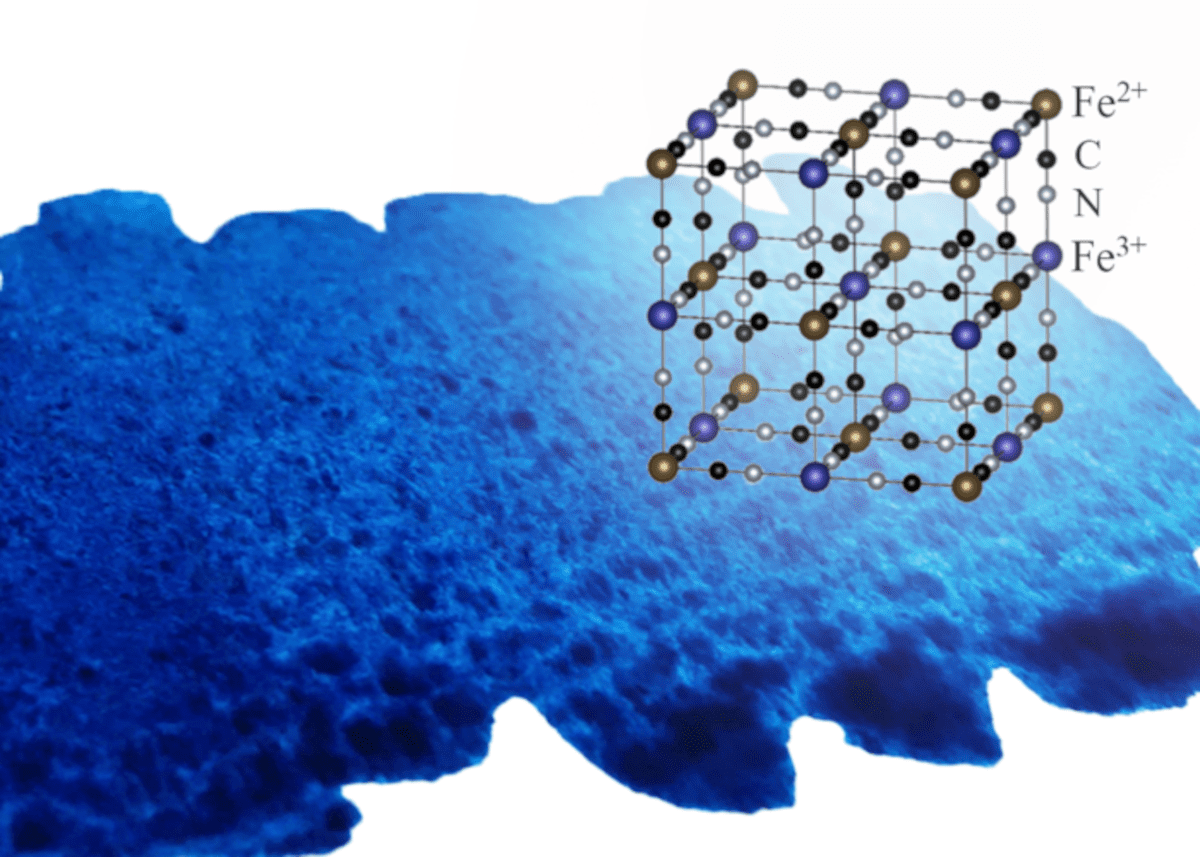

In the world of art, Prussian blue was originally used as a dye in paint and ink and has been used by such painters as Picasso, Van Gogh, and Hokusai for its dark blue color. However, in the world of chemistry, this pigment has another interesting property. Its nanometer-sized spaces (called nanospaces) have a jungle-gym-shaped lattice, which previous experiments found could uptake platinum-group metals. It was not clear, however, how the uptake of these multi-valent metals worked.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, a team consisting of Jun Onoe and Shinta Watanabe of the Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, in collaboration with Kenji Takeshita of Tokyo Institute of Technology, used X-rays and ultraviolet spectroscopy to learn more about the process. “I was surprised to discover that Prussian blue uptakes the platinum-group precious metals by substitution with iron ions in the framework while keeping the jungle-gym structure.” Professor Onoe explains. This mechanism allows Prussian blue to uptake more gold and platinum-group metals than conventional biobased absorbents.

Another benefit of the study was that it showed a way to solve one of the major problems of disposing of nuclear waste. Currently, spent nuclear fuel generated from power plants is taken to a reprocessing plant where the radioactive liquid wastes are converted into a glass-like state for geological disposal. In this process, leftover platinum-group metals often settle on the sidewall surface of the melter, therefore, creating an uneven distribution of heat. This imbalance affects the quality and stability of the vitrified objects and increases costs as the melter must be flushed before it can be used again.

“Our findings demonstrate that Prussian blue or its analogues are a candidate for improving the recycling of precious metals from nuclear and electronic wastes,” says Professor Onoe. “Especially when compared to conventionally used bio-based adsorbents/activated carbons.”

The loss of valuable metals in waste disposal is a serious problem, especially in the current situation of increasingly limited natural resources. By making the recycling of metals more efficient, Prussian blue or its analogue, promises to make the recycling more environmentally and economically friendly.

This work was financially supported partly by “The R&D program for advanced nuclear power systems” from MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology), and partly by Chubu Electric Power Co. Ltd.