A new study claims to settle a long-standing debate

Over the last decade, researchers have sounded the alarm on soil erosion being the biggest threat to global food security. As world governments moved to implement soil conservation practices, a new debate began: does agricultural soil erosion create a net organic carbon (OC) sink or source? The question is a crucial one, as carbon sinks absorb more carbon than they release, while carbon sources release more carbon than they absorb. Either way, the answer has implications for global land use, soil conservation practices and their link to climate change.

In a new study published on 16 February in the European Geosciences Union journal Biogeosciences, two researchers appear to show that the apparent soil organic carbon erosion paradox, i.e., whether agricultural erosion results in an OC sink or source, can be reconciled when we consider the geographical and historical context. The study was the result of a collaboration between UCLouvain, Belgium and ETHZurich.

The organic carbon cascade

Early studies assumed that a substantial fraction of soil organic carbon that is mobilized on agricultural land is lost to the atmosphere. They concluded that agricultural erosion represented a source of atmospheric CO2, which led to the notion of a win–win situation: soil conservation practices that reduce erosion result in healthier soils AND a large carbon sink.

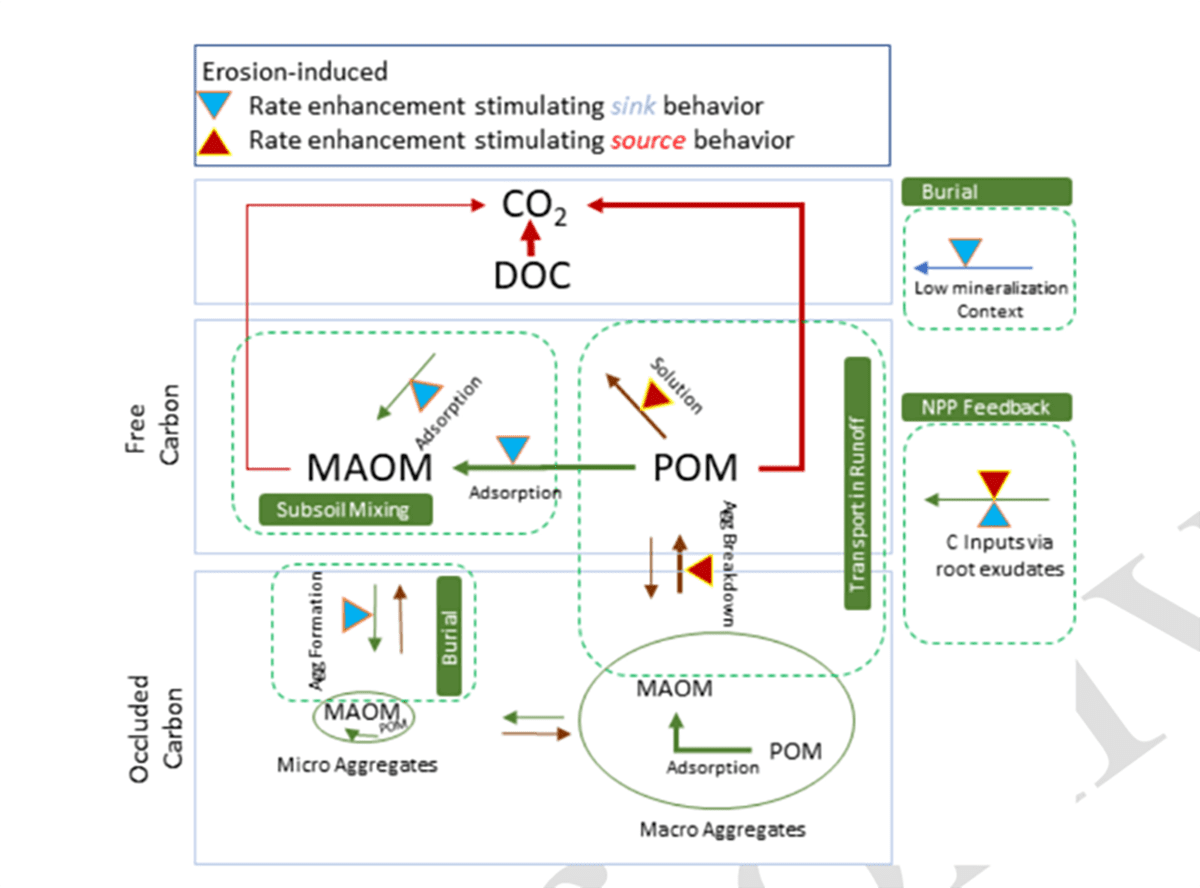

However, more recent studies have challenged this assumption and suggest a different pathway for the eroded organic carbon. They propose the concept of the “geomorphic OC pump” that transfers organic carbon from the atmosphere to upland soils recovering from erosion to burial sites where organic carbon is protected from decomposition in low-mineralization contexts. Along this geomorphic conveyor belt, the organic carbon originally fixed by plants is continuously displaced laterally along the earth’s surface where it can be stored in sedimentary environments. These studies argue that the combination of organic carbon recovery and sedimentation on land could capture vast quantities of atmospheric carbon, and so erosion may in fact represent an organic carbon sink.

“We demonstrate how these two competing views can exist at the same time and so this study offers an understanding of differences in perspective,” explains Kristof Van Oost from the Earth & Life Institute, UCLouvain.

Seeing the full picture for the first time

Johan Six from the Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and ETH Zurich says these latest findings are a first account of how all the different carbon dynamic processes induced by erosion interact and counterbalance each other in determining the net carbon flux from terrestrial environments to the atmosphere.

Six and Van Oost conducted a comprehensive literature review spanning 74 studies. Six explains the reason for the conflicting assumptions from previous studies. “We noticed that the perceived paradox was mostly related to not having considered the full cascade of carbon fluxes associated with erosion. This led us to thinking that it would be good to explain the complexity of the full carbon cascade.”

At the very centre of this paradox – they realised – is the fact that water erosion-induced processes operate across temporal and spatial scales, which determine the relationship between water erosion and organic carbon loss versus stabilization processes. Together they conceptualized the effects of the contributing water erosional (sub)processes across time and space using decay functions.

Timescales reconcile the paradox

Both researchers found that soil erosion induces a source for atmospheric CO2 only when considering small temporal and spatial scales, while both sinks and sources appear when multi-scaled approaches are used.

At very short timescales (seconds to days) erosion events shift a portion of the soil organic carbon from a protected state to an available state where it mineralizes to gaseous forms more rapidly. In contrast, studies considering erosion as a sink for atmospheric carbon typically consider longer timescales at which the geomorphic OC conveyor belt is operating.

The researchers emphasize the need for erosion control for the many benefits it brings to the ecosystem but recommend cross-scale approaches to accurately represent erosion effects on the global carbon cycle.

Looking to the future, Van Oost concludes, “Our insights into the effects of soil erosion on carbon storage are mainly derived from studies conducted in temperate regions. We now need new research on erosion effects in marginal lands but also tropical regions.”