A new detection method has been used to uncover increasing amounts of methane coming from wildfires, a source not currently accounted for in state-level emissions calculations in the US. The study was published in April in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Wildfires emitting methane is not new. But the amount of methane from the top 20 fires in 2020 was more than seven times the average from wildfires in the previous 19 years, according to the new study from the University of California at Riverside (UCR).

“Fires are getting bigger and more intense, and correspondingly, more emissions are coming from them,” said UCR environmental sciences professor and study co-author Francesca Hopkins. “The fires in 2020 emitted what would have been 14 percent of the state’s methane budget if it was being tracked.”

The state does not track natural sources of methane, like those that come from wildfires. But for 2020, wildfires would have been the third biggest source of methane in the state.

“Typically, these sources have been hard to measure, and it’s questionable whether they’re under our control. But we have to try,” Hopkins said. “They’re offsetting what we’re trying to reduce.”

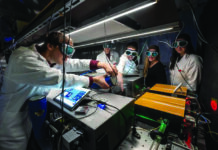

Traditionally, scientists measure emissions by analyzing wildfire air samples obtained via aircraft. This older method is costly and complicated to deploy. To measure emissions from 2020’s Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex in the Sierra Nevadas, the UCR research team used a remote sensing technique, which is both safer for scientists and likely more accurate since it captures an integrated plume from the fire that includes different burning phases.

The technique allowed the lead author, Isis Frausto-Vicencio to safely measure an entire plume of the Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex* gas and debris from 40 miles away.

“The plume, or atmospheric column, is like a mixed signal of the whole fire, capturing the active as well as the smoldering phases,” Hopkins said. “That makes these measurements unique.”

Rather than using a laser, as some instruments do, this technique uses the sun as a light source. Gases in the plume absorb and then emit the sun’s heat energy, allowing insight into the quantity of aerosols as well as carbon and methane that are present.

Using the remote technique, the researchers found nearly 20 gigagrams of methane emitted by the Sequoia Lightning Fire Complex.

This data matches measurements that came from European space agency satellite data, which took a more sweeping, global view of the burned areas, but are not yet capable of measuring methane in these conditions.

If included in the California Air Resources Board methane budget, wildfires would be a bigger source than residential and commercial buildings, power generation or transportation, but behind agriculture and industry.

In 2015, the state first established a target of 40 percent reduction in methane, refrigerants and other air pollutants contributing to global warming by 2030. The following year, in 2016, Gov. Jerry Brown signed SB 1383, codifying those reduction targets into law.

The reductions are meant to come from regulations that capture methane produced from manure on dairy farms, eliminate food waste in landfills and other measures.

“California has been way ahead on this issue,” Hopkins said. ‘We’re really hoping the state can limit the methane emissions under our control to reduce short-term global warming and its worst effects, despite the extra emissions coming from these fires.”

*A complex of the two August 2020 California wildfires, burning in Sequoia National Forest and adjacent areas.