Vince Zabielski writes

In February, Labour’s Kier Starmer faced criticism from the Tories for cutting their green spending plan from £28bn per year to £4.7bn. What fate awaits the power sector under what will likely be a Labour government, and why is the question so important?

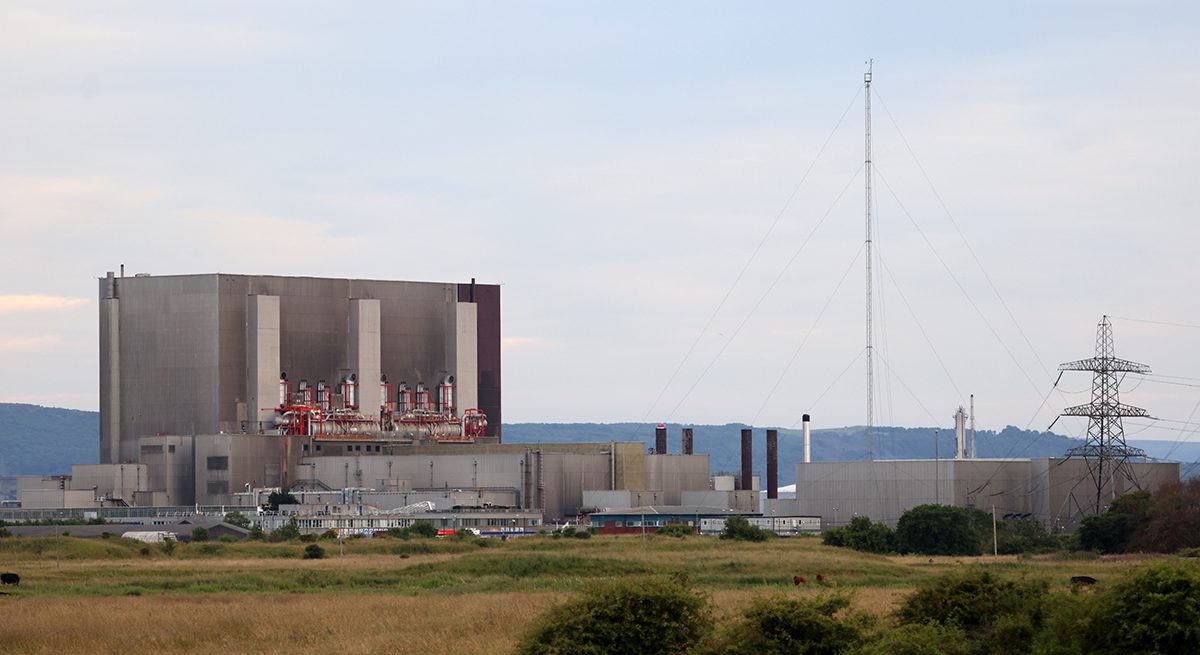

To begin with, there is an upcoming imbalance in electricity supply and demand. Electricity supply in the UK is shrinking, while demand is increasing. Coal plants have largely been phased out and four out of five of the UK’s nuclear plants are scheduled to shut down before 2028. Amongst these is the Hartlepool nuclear plant, which is scheduled to permanently shut down this in March 2026, representing a loss of 1190 megawatts, while Heysham 1’s 1155 megawatts will also be gone in 2026. Torness and Heysham 2, at a combined 2354 megawatts, will come offline in 2028. That’s 4.7 gigawatts of nuclear power lost between now and 2028, and Hinkley Point C won’t be online until after 2030 at the earliest. Moreover, Hinkley will only make up 3.2 gigawatts, which will leave us with less nuclear power in 2030 than we had in 2023.

Meanwhile, demand for electricity is increasing, in part due to growing demand from electric cars and heat pumps. The peak demand occurs in the winter evenings when everyone returns home, turns that kettle on, and puts their car on the charger.

At any point in time the amount of electricity being supplied to the national grid must exactly equal the amount of electricity being drawn from the grid. Keeping this delicate balance was easier in the past when the electricity was generated by coal, gas, and baseload nuclear. The fossil power plants could easily be ramped up or down to match the demand for electricity at any time, so it was easy to keep supply and demand in balance.

Renewables, however, are an entirely different kettle of fish because their output literally depends on whether the wind is blowing, or the sun is shining. This is what is called the “intermittency problem.” There inevitably will be times when the wind isn’t blowing, or the sun isn’t shining. Even worse, there will be times when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining. The Germans have even invented a word for when this happens: dunkelflaute, which translates into English as something like “dark wind lull”, or the more poetic “dark doldrums.” The problem is that demand for electricity doesn’t change during these dunkelflauten, and in some cases, it may even increase. As mentioned, people still want to put the kettle on when they get home on those sunless British winter evenings. With no sunlight during these times (in other words, when it is dunkel outside) we’re already halfway there to our dunkelflaute, just when we need electricity the most.

Because of this intermittency, a renewable megawatt is not the same as a fossil or nuclear megawatt in the eyes of National Grid ESO, the system operator for the UK’s electrical grid. The ESO accounts for the relative reliability of various energy sources using a “de-rating factor”, which is a measure of the probability a particular power source will be available when the ESO asks for it. Gas turbines and other fossil plants top the list at a 95% de-rating factor – you start your gas turbine and you’re off to the races. Nuclear is at a respectable 78%, while onshore and offshore wind trail far behind at 8% and 11% respectively.

Practically speaking, this means that for every megawatt of gas or coal installed capacity, you need almost 12 megawatts of installed onshore wind capacity to get the same reliable power output. If you want your reliable megawatt to be carbon-free, 1 megawatt of nuclear capacity is worth almost 10 megawatts of on-shore wind or 7 megawatts of offshore wind. The viability of solar energy, meanwhile, warrants little discussion. During the London winter I don’t expect the sun to recharge the luminescent hands on my wristwatch, let alone power a steel mill.

When demand exceeds supply, the lights go out. Objectively, it really is too late to avoid the upcoming power crunch, and it’s now a question of how long the crunch will last. There is a likelihood that ordinary Britons may need to live with electricity rationing and rolling blackouts in the upcoming years. Investment in new nuclear has never been more important. Let’s hope whoever is in Number 10 next year opens their cheque book after all.