Danish researchers say they have demonstrated that it is possible to remove most of the carbon dioxide (CO2) from the emissions of a waste incinerator. By demonstrating the viability of the process, a key technology in the fight against climate change is surely awaiting deployment, they suggest. A pilot plant has been operational in Copenhagen for several months and a novel gas monitoring technology has been used to optimize the efficiency of the plant. Instrumentation firm Vaisala writes.

If global leaders are to deliver on their commitments to achieve net zero, one of their key objectives will be to develop and exploit decarbonisation technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). To that end, researchers from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) are working with a highly innovative waste incineration plant in Copenhagen to develop a process that is able to capture CO2 from its emissions. The project is utilising advanced gas analyzers from Vaisala to measure carbon capture efficiency and therefore CCUS viability.

The researchers have developed a pilot plant to remove CO2 from the emissions of the incinerator at the Amager Bakke Waste-to-Energy Plant, which is one of the largest combined heat and power (CHP) plants in northern Europe, with the capacity to treat 560,000 tonnes of waste annually. Developed by the Copenhagen-based waste management company ARC (Amager Ressourcecenter), which is jointly owned by five Copenhagen-area municipalities, the CHP plant features a number of innovations including a rooftop artificial ski slope, which is part of an outdoor activity centre known as CopenHill.

The pilot plant was developed to capture CO2 from the emissions of processes such as wastewater treatment, biogas production, anaerobic digestion and waste incineration.

However, the researchers are also investigating the ways in which CO2 can be both captured and utilized. Prior to its installation at Amager Bakke, the pilot carbon capture plant was operated at a wastewater treatment plant. “The technology itself is not new,” explains Jens Jørsboe, a researcher from the DTU, “However, the focus of our work has been to lower the cost of carbon capture, so that it can become economically feasible.”

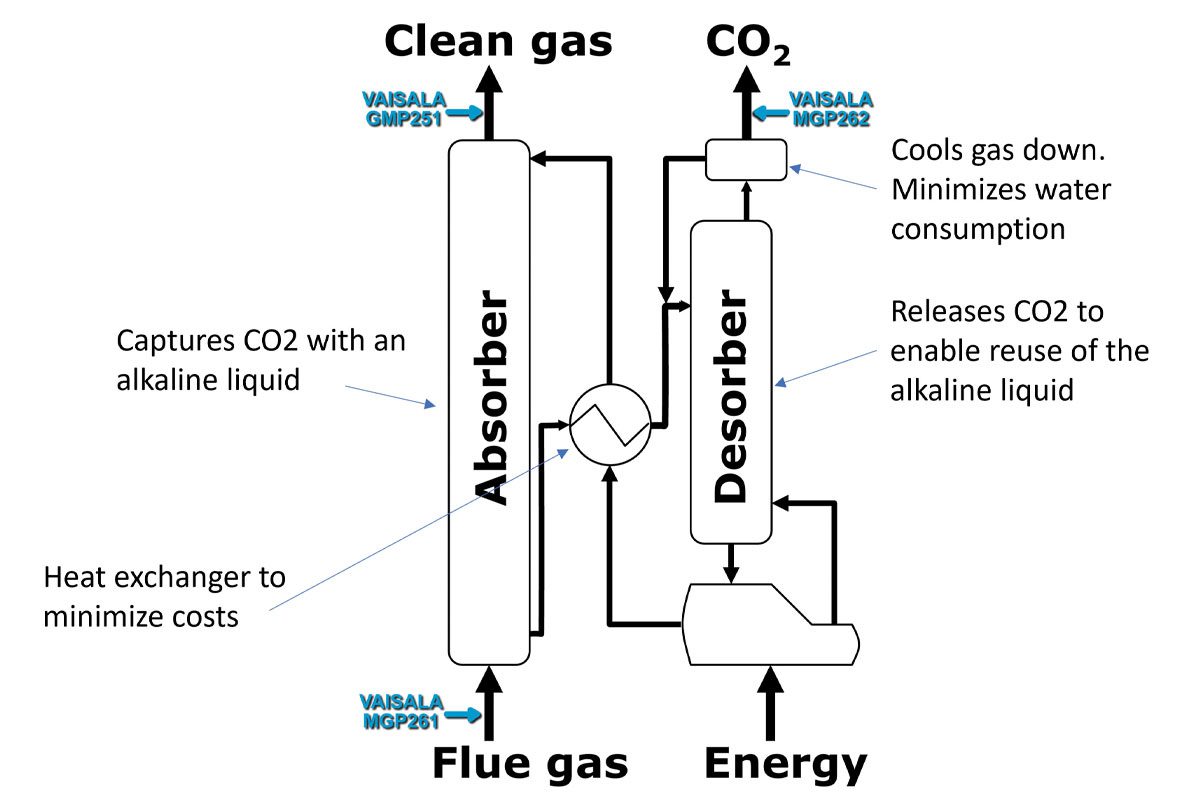

Exhaust gas from the Amager Bakke incinerator is passed through an electrostatic precipitator (ESP) to remove particulates, NOx compounds are removed by selective catalytic reduction (SCR) and a scrubber removes oxides of sulphur. High levels of CO2 remain in the flue gas and the main purpose of the pilot carbon capture plant is to investigate the feasibility of its capture.

To achieve this, the gas is passed upwards through a column packed with beads and a monoethanolamine (MEA) solvent which scrubs the CO2 from the gas. The solvent is then passed to a desorber which removes the CO2, which is now almost pure, and regenerates the MEA for re-use. As a research project the produced CO2 is currently still vented to air, but on a commercial basis there are many different industrial applications in which CO2 can be utilized. For example, CO2 can be reacted with hydrogen in the Sabatier process to produce methane and water, at elevated temperature and pressure, in the presence of a nickel catalyst.

This can be a green method for manufacturing fuel if the hydrogen is generated by electrolysis using renewable energy.

CO2 is also used in a wide variety of other industries including food and beverages, refrigeration, medical, horticulture, firefighting, welding etc., so a variety of potential markets are available if CO2 can be produced on a commercial quality and scale.

Monitoring CC efficiency

The optimization of the carbon capture process can only be achieved if CO2 concentrations can be continuously monitored both before and after the carbon capture process. It was fortunate therefore that the world’s first inline CO2, humidity and methane monitor was developed by Vaisala in Finland prior to the pilot plant construction.

Exhaust gases from incinerators can be corrosive and potentially explosive, so in the past it has not been possible to conduct in-line monitoring. Until recently, the only solution was to extract samples for analysis outside of the process, but this method is not suitable for process control and optimization, and has a number of inherent flaws, such as the need to remove humidity from the sample line and a requirement for frequent re-calibration.

The development of Vaisala’s multi-gas probe, the MGP261, resolved all of these monitoring challenges, especially when it was followed by a sister product the MGP262, which was adapted for measuring high concentrations of CO2 and was therefore ideal for the continuous inline monitoring of almost pure CO2 after the pilot plant’s desorber.

The pilot plant employs three Vaisala probes in total, with the MGP261 monitoring incoming incinerator exhaust gas, and the MGP262 measuring the purity of the extracted CO2. The third probe is a Vaisala CARBOCAP® CO2 probe, the GMP251, which checks the levels of CO2 (after carbon capture) in the pilot plant’s exhaust gas.

All three monitoring probes contain CARBOCAP® technology which utilizes an electrically tunable Fabry-Pérot Interferometer (FPI) filter. In addition to measuring the target species, the micromechanical FPI filter enables a reference measurement at a wavelength where no absorption occurs. When taking the reference measurement, the FPI filter is electrically adjusted to switch the bandpass band from the absorption wavelength to a non-absorption wavelength. This reference measurement compensates for any potential changes in the light source intensity, as well as for contamination in the optical path, which means that the sensor is highly stable over time.

Within the MGP261 and the MGP262, humidity and CO2 are measured with the same optical filter, and a second optical channel measures methane. In many ways, this combines the analytical power of a laboratory spectrometer with the simple, rugged design of an industrial process control instrument.

“We have been delighted with the accuracy and reliability of the multigas probes,” says the firm’s Jens Jørsboe, “not least because they have enabled us to learn a great deal about the management of flue gas from waste incineration.

“The technology employed by the Vaisala probes is also helping to minimise operational costs because by effectively calibrating themselves the probes’ service requirements have been minimal and downtime is avoided.”

What’s next?

With the benefit of continuous inline monitoring, the researchers have been able to optimize carbon capture performance following an evaluation of twelve different pilot plant configurations. Having proven the viability of the carbon capture process, the next step was to evaluate the relative advantages of carbon storage and utilization. Jens Jørsboe says: “At the moment, utilization of CO2 is the more expensive option because of the costs associated with the required further refinement of the CO2, so the owners of the Amager Bakke plant are planning to apply for 1.5 billion DKK ($230 million USD) for a CCS plant capable of capturing 500,000 tonnes of CO2 per year – if the right regulatory framework and sufficient funding is provided by the Danish state. This plant would employ the same amine scrubbing process that has been proven by the pilot carbon capture plant.”

The incineration of 1 tonne of municipal waste (MSW) is associated with the release of between 0.7 and 1.7 tonnes of CO2, depending on the content of the waste. Consequently, energy generation from waste incineration is more carbon intensive than the burning of fossil gas, so carbon capture offers an opportunity to manage the growing requirement for municipal waste treatment without generating unacceptably high levels of GHGs.

Looking forward, Jens believes that this technology could be applied at every waste incinerator in the world, which according to the latest data from ecoprog represents around 2,500 WtE plants, with a disposal capacity of around 400 million tonnes of waste per year.

In addition, it should be possible to harvest residual heat, which could be transferred to local industry or to a district heating network.